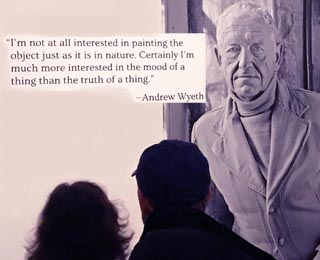

Entrance to the Wyeth Exhibition, Andrew tells visitors, "I'm not at all interested in painting the object just as it is in nature. Certainly I'm much more interested in the mood of a thing that the truth of a thing ."

-- Andrew Wyeth |

Lobsterman Walt Anderson, 1937 ... early in his career, Wyeth was recognized for his mastery of painting with wet transparent watercolor, as Maine's Winslow Homer had done. Finding this style unstatisfying because it came too easily to him, Wyeth moved to a drybrush technique.

Coming Storm, 1938 ... Here, with wet into wet, Wyeth daringly and darkly portrays the fierceness of this coastal storm.

|

Lobsterman Walt Anderson,

1937

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA |

Coming Storm, 1938

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Clump of Mussels, 1939

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Clump of Mussels, 1939 ... Andrew Wyeth wrote, "Nature is not lyrical and nice. In Maine I'd lie on my belly for an hour watching the tide rising, creeping slowly over everything -- the shells that were drying in the sun. Nothing can stop it -- amazing -- sad."

This exhibition was wildly popular. We vistied it on January 6, a Saturday, a week before it closed --and the lines were long.

|

Visitors to the exhibition studied paintings in detail, discussed among themselves newly discovered details and nuance. There seemed to be a genuine interest, a visual dialog happening between Wyeth and each of his viewers. This was far more than a gathing of people visiting an exhibit because it was the in-thing to do.

|

Pan of Seattle Art Museum visitors to Wyeth Exhibition |

Winter Fields, 1942

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY |

Winter Fields, 1942 "In the midst of WWII, Wyeth said, "You don't have to paint tanks and guns to capture war. You should be able to paint it in a dead leaf falling from a tree." In remote Chadds Ford, PA, Wyeth painted war. He assigned roles for nature and landscape to play in poignant narratives of loss and death. Here, a dead crow is frozen stiff in a field drained of color, fallen like so many soldiers in the killing fields of any war."

|

Spring Beauty, 1942 Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery,

University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE |

Spring Beauty, 1943 "Always sharpening his hyperrealism, Wyeth refined an approach to watercolor painting, one related to the slow, meticulous process of painting with egg tempera. He called it "drybrush," and though other artists employed such a technique, the term is always associated with Wyeth. Drybrush describes perfectly the method; his soft brush was filled with color but wrung out and pressed into a point, thus enabling the artist to draw with paint--to render detail and build up textures by layering small strokes of dry color." Although this photo is small, the painting was large and showed in great detail the wrinkles of the this tree speading roots littered with fall's leaves. |

Public Sale, 1943, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA |

Night Hauling, 1944

Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, ME |

Public Sale, 1943 ... Andrew's father N.C. Wyeth never understood why his son chose an unyielding medium to paint somber-colored landscapes in gray moods. But Andrew knew Chadds Ford; it was his home, a place he was deeply rooted. Public Sale shows a familiar scene from the 1940's, a farm being foreclosed. Even though the farm was centuries old, its continued existance was tenuous.

Night Hauling, 1944 ... Under cover of night, Wyeth's friend Wes Anderson steals a lobster pot belonging to another fisherman. Stealing lobster pots was dangerous business, but Wyeth found it enchanting. Each dip of the oar seemed to pierce a star lighted sky. "The water, illuminated by mysterious bioluminescence of plankton and sea creatures makes it seem like another cosmos."

|

Mother Archie's Church, 1954 ...

Wyeth may have seen the decaying Mother Archie's church in 1945, a crumbling monument to peace in a time of war.

The old Quaker meetinghouse and school stood on scene of the bloody Battle of the Brandywine in 1777, and now it demarcated the implied border between Chadds Ford’s old European immigrant families and its black residents in what the locals referred to as Little Africa.

|

Mother Archie's Church, 1945

Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA |

The eighteenth- century stone octagon building was acquired in 1871 by The Reverend Lydia Archie, the first ordained female preacher in the African Union Methodist Protestant Church, as a home for a congregation. Wyeth remembered attending services here on occasion, but eventually the old building just collapsed.

|

Hoffman's Slough, 1947

Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY |

Below Dover, 1950

Collection of Phyllis and Jamie Wyeth |

Hoffman's Slough, 1947 ... "The bloody Revolutionary War battle of Brandywine took place in the mudflats known as Hoffman's Slough. Wyeth regularly walked the ridge where the evening's shade

|

passed over the valley like the eyelid of night. To Wyeth, this scene had death moving in."

Below Dover, 1950 ... The painting of a Friendship sloop, a distinctive and classic Maine fishing boat, is trapped is a sea of marsh grasses, its bowsprit pointing toward the sea. Like Christina's World, showing Christina Olson crawling slowly towards home, this land-trapped vessel longs to return to the sea.

|

Northern Point, 1950

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT |

Spindrift, 1950

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH |

Trodden Weed, 1951

Collection of Phyllis and Jamie Wyeth |

Incoming Fog, 1952

Private Collection |

Northern Point, 1950 ... This shows a portion of the roof of Wyeth's friend, Maine lobsterman Henry Teel. Seven generations of Teels lived in this house, built in part from timbers taken from the wreckage of a man-of-war. Wyeth saw in the old lobsterman's cragy weathered face reflections of the island's distinctive rough textures, here illustrated by the old slate-roofed house and the rocky ledges. The lightning rod rising from the roof resembles the buoys marking Teel's lobster traps.

|

Spindrift, 1950 ... Wyeth wrote, "Hen (Henry Teel) would go out early to tend his lobster traps, and I could hear his squeaking oarlocks and the sound of a trap hauled up and let drop down. He knew every bit of water he rowed so well it was just a part of him. He'd land on the beach, step the oars, and get out all in one motion ... The dory was like a child to him. I painted it as a portrait of Hen."

Trodden Weed, 1951 ... Wyeth painted himself here, focused now on the world at his feet. He wears swashbuckler’s boots that had once been props for his father’s teacher, the illustrator Howard Pyle. In January 1951, he had undergone lung surgery that nearly killed him. “You can be in a place for years and years and not see something,” the artist once explained, “and then when it dawns, all sorts of nuggets of richness start popping all over the place. You’ve gotten below the obvious.”

Incoming Fog, 1952 ... This tattered curtain hung over a side light at the front door of the Olson house in Maine. Decades of wind and incoming fog had shredded the delicate lace, and now it moved like a ghost from the house’s past. Wyeth said, "I had this very deep feeling that it would not be long before this fragile, crackling-dry, bony house disappeared. I’m very conscious of the ephemeral nature of the world. There are cycles. Things pass. They just do not hold still. I think probably my father’s death did that to me.

|

April Wind, 1952 ... Wyeth was fascinated by James Loper's lanky posture and far off look, a gaze always searching. In this scene from the rear, we cannot see his face, obscured by the turned up collar of his coat. He's private and elusive, part of Wyeth's fascination.

Tarpapering, 1952 ... Ben Loper and his son James were often seen on their roof putting down tarpaper.

|

April Wind, 1952

Wadsworth Antheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT |

Tarpapering, 1952, Private Collection |

Miss Olson, 1952, Private Collection |

Snow Flurries, 1953, Private Collection |

Winter Light, 1953

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH |

Miss Olson, 1952 ... Betsy Wyeth wrote, "The key to the Olson pictures is Andy’s relationship with Christina—absolutely at ease with him. While she was posing, he said, “You have the most marvelous end to your nose, a tiny delicate thing that happens. . .” With a cloth he carefully wiped all the corners of that great face, all around the little places, around the lips, the ears. He said, “I’ve never felt such delicacy. You know, she’s like blueberries to me."

Snow Flurries, 1953 ... The landscape around Chadds Ford was more to Andrew than just landscape. Wyeth claimed that he could stare into the past in the Chadds Ford hills, their landmarks whispering of human presence: here an old wagon path now leads to nowhere. In the far-off distance, on the horizon at center, is a snow-covered sliver of the landmark that stood always like the round-topped grave of his dead father—Kuerner’s Hill.

Winter Light, 1953 ... This scene is of a lean-to behind the farmhouse next door to Wyeth’s studio in Chadds Ford. Wyeth told his biographer that he chose this watercolor himself to honor poet Robert Frost—a group of Frost’s friends had asked to purchase a Wyeth painting as a gift on the poet’s eightieth birthday. Wyeth loved Frost’s poetry, but he declined a request later on to paint the great bard’s portrait: “The art, the poetry, is the purest form. Not the man.”

|

James Loper, 1952

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA |

Teel's Island, 1954, Private Collection |

James Loper, 1952 ... Again, James Loper, ... Loper always fascinated Wyeth by his characteristic far-off look, and everything about this composition sends our gaze up to Loper’s searching eyes. His frame seems too large to be contained in his old frayed clothes and shoes. Loper’s tall body is enclosed by the graceful lines of a pair of old scythes, symbols of death that Wyeth

|

assigns to this elusive man, seemingly from a time long ago, a mystic of sorts who was known to roam around Chadds Ford in silent midnight rambles.

Teel's Island, 1954 ... Wyeth explains this painting ... "Henry Teel had a punt, and one day he hauled it up on the bank and went to the mainland and died. I was struck by the ephemeral nature of life when I saw the boat there just going to pieces."

Nicholas, 1955 ... Andrew Wyeth's younger son, Nicholas.

|

Nicholas, 1955

Collection of Nicholas Wyeth |

Karl's Room, 1954

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston |

Roasted Chestnuts, 1956

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA |

White Shirt, 1957

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Karl's Room, 1954 ... One of the earliest of the Kuerner farmhouse paintings is this one of Karl’s room, where his rifle and animal heads were kept. Wyeth was fascinated by Kuerner as a killer. He had been a machine gunner in the German army in the First World War and murdered Americans.

|

Karl was hardened by war and the fight for survival from season to season on the farm, and he could easily commit beastly things, like nonchalantly shooting and butchering deer and small animals.

Roasted Chestnuts, 1956 ... Allen Messersmith, a neighbor boy in Chadds Ford, was a lifelong friend of Andrew Wyeth and an occasional model. Here he sells chestnuts at the side of the highway. Everything about the skinny boy and his enterprise suggests hard times. He wears a frayed World War II Eisenhower jacket, most likely from someone’s discards. Messersmith was not a veteran, which we might assume from the picture, but he was a young man made old by circumstances before his time. He lived by himself in an old house near the Wyeths, a recluse his entire life.

White Shirt, 1957 ... Andrew Wyeth used this painting to teach about his ideas of watercolor, "Now about watercolor. The only virtue to a watercolor is to put down an idea very quickly without too much thought about what you feel at the

|

River Cove, 1958

Portland Museum of Art, Portland, ME |

moment. . . . With watercolor you can pick up the atmosphere, the temperature. . . . Watercolor perfectly expresses the free side of my nature."

River Cove, 1958 ... Wyeth felt that to look into water is to see the sky. He often saw landscape as a way to see time itself. When he looks at this sandy shore, he senses the once living things that have been deposited here and the tracks of a heron that will be washed away with the tide.

Untitled Study in Kuerners House, 1958 and Bushel Basket Study, 1958 ... The exhibition included studies done by Andrew, keen always to explore possibilities in depicting compositional elements.

|

Untitled Study in Kuerner's Hosue, 1958

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Bushel Basket Study, 1958

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Morning Sun, 1959 (study for That Gentleman)

Collection of Andy Weston Fowler,

Lookout Mountain, TN |

Chester County, 1962

Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Frank E. Fowler |

That Gentleman, 1960

Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX |

Morning Sun, 1959 (study for That Gentleman), Chester County, 1962 ... and That Gentleman, 1960 ... Tom Clark lived in Chester County, the oldest county in the state. As time passed Tom Clark by, the region became part of Philadelphia's elegant suburbs, but Tom Clark's Chester County home was a three room house without running water. Wyeth admired Clark's dignified bearing and saw him as a true country gentleman.

|

Willard, 1959

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Lime Banks, 1962, Private Collection |

Willard, 1959 ... Andrew Wyeth explained, "Willard Snowden knocked at the studio door one late fall day in 1958 asking for work. He ended up living in the studio for fifteen years, becoming a very important model."

Lime Banks, 1962 ... Typical for Wyeth, he always saw the story behind the landscape. Even a dry white lime bank could possess hidden meaning and a rich cinematic quality for Wyeth the dreamer. Here were Maine’s seafarers, he said, whose clipper ships carried lime to ports around the world; here were their white clapboard houses with garret windows where women waited for the sight of those ships returning home. This lime bank spoke of Maine’s former glory: “the crown of the king of nature,” Wyeth described it, now covered as if in cobwebs. He saw it flashing bright white in the moonlight. Returning to his studio that night, he drew the impression right on the wall, getting it down quickly to preserve it for painting.

|

British at Brandywine, 1962

Private Collection |

Garret Room, 1962

Collection of Nicholas Wyeth |

Adam, 1963

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA |

British at Brandywine, 1962 ... Since his boyhood, Wyeth had a collection of toy soldiers. They remained with him in his studio.

|

Here, some seem to come to life on a windowsill in an old mill building which Betsy Wyeth renovated for a family home.

Garret Room, 1962 ... Wyeth was inclined to artistically view sleep as death. Here, Tom Clark is napping on his grandmother's prized quilt. Wyeth paints him as if he were lying in state.

Adam, 1963 ... Adam raised chickens and pigs on his Chadds Ford farmstead. Wyeth said, "He could have been a Mongol prince—or Old Kris coming toward me, with all those jingles and safety pins and things on him."

|

The Patriot, 1964

Collection of Nicholas Wyeth |

Room after Room, 1967

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

The Patriot, 1964 ... Here is one of Wyeth's Maine friends, Ralph Cline. A veteran of the the trenches of World War I, Wyeth claimed to hear "the thunder of the Meuse-Argonne" and smell "the dirt and mud Ralph stood in while in the trenches."

Wyeth was fascinated and and often pondered the acts men were capable of carrying out when motivated by patriotism. Karl had stood in the trenches as men died. His portrait was deeply personal for Wyeth, and he never parted with it.

Room after Room, 1967 ... Wyeth sensed these were his last weeks with the Olsons.

|

He painted her obsessively. Here he glimpsed her as she sat quietly and alone in a distant room. Wyeth views here through the extent of her interior world, each successive room.

|

Alvaro and Christina, 1968 ... Alvaro Olson died Christmas night, 1967 and Christina passed just weeks later in January, 1968. In the summer of '68, Andrew visited the Olson house and felt their loss. Alvaro's empty vegetable basket and Christina's washrags and apron hung on nails.

Slight Breeze, 1968 ... A stark white wall with an outdoor bell and clothesline.

|

Alvaro and Christina, 1968

Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, ME |

Slight Breeze, 1968, Private Collection |

Wyeth said, "The scene reminded me of my daughter-in-law Phyllis on her crutches. The bell seemed to me to be her wearing a characteristic big hat. It’s early spring. There are wild flowers. The wind is blowing around the corner. I love the way the light hit the white-painted bell and the building beside it."

|

The Finn, 1969

Collection of Shelly and Tony Malkin |

The Virgin, 1969

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA |

Siri, 1970

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA |

The Finn, 1969 ... The man pictured in The Finn is George Erickson, Siri Erickson's father. He was born the same day and year as Karl Kuerner back in Chadds Ford, and Wyeth found him equally dark.

|

Due to the coincidence of sharing the same birth date, Wyeth felt fated to meet George Erickson. The Ericksons lived not far from Christina and Alvaro Olson in Cushing, Maine. The Ericksons lived in a primitive house, apart from the modern world, with no indoor plumbing and few comforts.

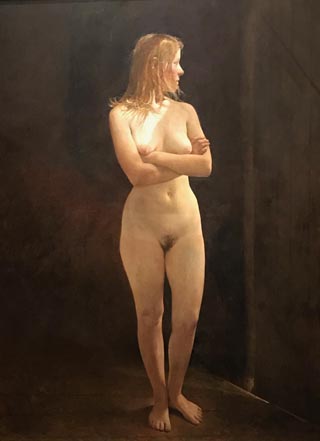

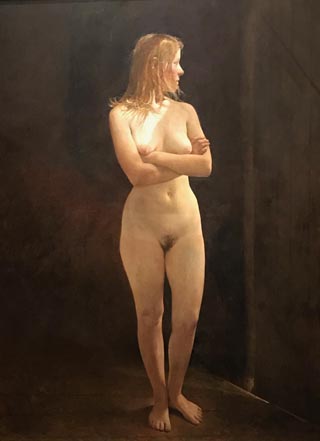

The Virgin, 1969 ... If painstaking realism was associated with emotional detachment, Wyeth was determined to show that

it could be otherwise. He dedicated himself to exploring the shock value of an erotic subject with his model Siri Erickson, beginning in 1968. Although the Siri nudes might seem like a sudden change of course for Wyeth, he thought they flowed naturally from the Christina Olson portraits, paintings that were shocking in another way for their discomforting coarseness. Wyeth discovered Siri just as Christina was dying. Death as a controlling obsession was set aside now: “I’ve found something else that excites me,” he said.

Siri, 1970 ... In the Fall of 1967, Wyeth had a chance encounter with someone who would become his new model. Siri, only 13 at the time of their meeting, took Wyeth's art into unexplored realms. She proved to be a catalytic force, "a burst of life, like a spring coming through the ground, a rebirth of something fresh out of death," meaning Christia Olson's death.

|

Evening at Kuerners, 1970

Collection of Nicholas Wyeth

|

Evening at Kuerners, 1970 ... “What I am doing now is so personal to me, it has nothing to do with Kuerners as a specific place anymore,” Wyeth would say in 1976.

|

Anna Kuerner, 1971

Collection of Shelly and Tony Malkin |

The painting Evening at Kuerners was not simply about a time of day, a quality of light, and a landscape. Initially, Wyeth sought to capture something of what he felt about the dying Karl Kuerner: the light in the ground-floor window was, to Wyeth, Kuerner’s flickering soul. But soon the painting came to be a repository of other sensations. Just looking at it, Wyeth could enter at will his own private world, feeling “how the steps curve up to the attic, and the cool air that comes out of that door when you open it.” We now know that at the time he recalled this sensation he was painting Helga in that upstairs room in secret.

Anna Kuerner, 1971 ... Anna Kuerner was elusive, a tiny woman who moved in and out of vision like a darting bird and spoke only German. She had never wanted to pose, but one day she surprised Wyeth by relenting. Over the next two weeks he made studies of her in watercolor, pencil, and tempera.

|

Sea Dog, 1971

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection

|

Black Velvet, 1972, Private Collection |

Sea Dog, 1971 ... Wyeth’s portrait study of his close friend Walt Anderson is as fresh and direct as a snapshot. Wyeth and Anderson had grown up together in their summers

|

in Port Clyde, Maine. The artist painted Anderson many times throughout their lives, watching Anderson’s character develop and coming to the realization that the lines of Anderson’s weather-beaten face recorded something of Wyeth’s own life, too, so close were the two men for so long.

Black Velvet, 1972 ... Here the sleeping Helga occupies a strange, incongruous place in an artist’s studio. Her meticulously rendered body now lives in the realm of art—the connection to Edouard Manet’s famous nude Olympia, with her black velvet ribbon choker, is often commented upon. Helga’s body floats as though on a dark sea. She glows by contrast. Wyeth’s precise drybrush watercolor technique forces us to stare. This is the equivalent of a filmmaker’s long, long static close-up that arouses all the viewer’s senses. His hyperrealism is obsessive, even possessive. Whatever the precise nature of the relationship he had with Helga, Wyeth shows us here that painting her was, in itself, an intimate act. (Refer to our January article, scanning down to comments about Wyeth's painting, Lovers, 1981.)

|

Ericksons, 1973

Michael Altman Fine Art & Advisory Services LLC,

New York, NY |

Wolf Moon, 1975

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Anna Climbing the Stairs, 1975

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

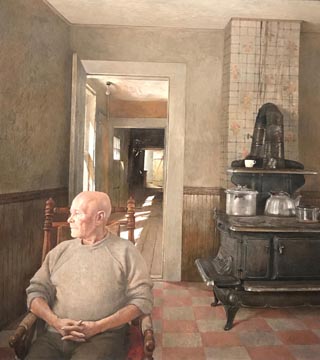

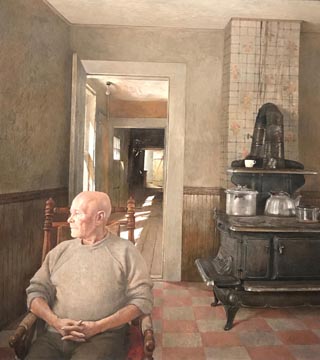

Ericksons, 1973 ... When Wyeth painted this portrait of George Erickson, Siri’s father, in the kitchen of his old house,

|

Wyeth was five years into his artist-and-model relationship with the girl who had drawn him to the primitive confines of the Erickson’s place time and time again. Wyeth said he always thought about secrets that the aloof old Erickson kept and about secrets concealed behind the closed doors. At this time Wyeth was deep into his own consuming secret—he was making often-erotic studies of a Chadds Ford model, the married Helga Testorf, without the knowledge of his wife or of Testorf’s husband.

Wolf Moon, 1975 ... A January full moon, which farmers call a wolf moon, drew Wyeth out for the midnight ramble that produced this watercolor. In that light at that hour, the strangeness of the Kuerner farm was only heightened. Wyeth was surprised when he came upon it to hear the sound of what he knew had to be tiny Anna Kuerner chopping kindling inside the woodshed for the breakfast fire. “I stood there in the crisp, chill moonlight, entranced,” he said. Back in the studio, he painted this recollection of the light and sound—completing it in less than an hour, using “a great deal of luxurious black in order to make the thing really shout” and leaving the unpainted white of the paper to impart the cold light. The painting embodies Wyeth’s thoughts, he said, of what was happening inside the house, unseen, as the frail but unstoppable Anna, now seventy-seven years old, worked heroically for her family and dying husband.

Anna Climbing the Stairs, 1975 ... Andrew wrote, "I noticed her going up this circular staircase on the second floor that goes up to the attic where I painted Karl with the iron hooks. . . . Over the years, I’ve been fascinated by things disappearing up that staircase. It seemed to me to say something about the ephemeral nature of life itself. The first sketch I made of Anna Kuerner darting up the stairs was made from memory. I spent a month and a half just watching her disappear . . . I couldn’t get her to pose, so I just sat there and waited.

|

The German, 1975 ... Karl Kuerner was a German Army machine gunner. With Wyeth's imagination substituting for a model, he painted Kuerner in his soldier's coat and helmet, this time as an old man playing the part of his younger self. Wyeth remarked that Karl's helmet spoke volumes of his experience in the Black Forest during WWI.

|

The German ,1975

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection

|

Flint Study, 1975

Collection of Shelly and Tony Malkin |

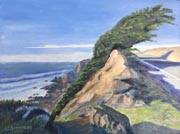

Flint Study, 1975 ... In Wyeth's imagination, things like rocks or boats could be metaphorical portraits or self-portraits. He often drew parallels between Maine's rocky shore to the weathered Maine lobstermen and fishermen he knew, especially his close friend, Walter Anderson.

|

Home Comfort, 1976

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Spring, 1978, Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA |

Home Comfort, 1976 ... Andrew said of this painting, "I never consider these studies as drawings. All I’m doing is thinking with my pencil and brush. . . . There would have been a time when I would have made hundreds of close, methodical, even oddly dull drawings of an object when I was learning to catch a subject off balance. And slowly, one learns to know anatomy, to know structure, proportion, perspective, when to modify, when not to, when to exaggerate, when to thin down. These are all things an artist should train himself to do so that at the right moment, the decisive moment, one is there to catch it, whether it’s imaginary or graphically right there in front of you."

Spring, 1978 ... Here, Wyeth offers a nightmarish vision of his dying friend, Karl Kuerner. He imagines Karl covered in ice on Kuerner's Hill, a landmark which haunted Wyeth ever since his father, N.C. Wyeth, died nearby. In the months before Kuerner succumbed to leukemia, in January 1989, Wyeth regarded his friend in such a suspended state, his body lifeless but his mind active and his visions clear. The dying man once lapsed into a waking dream of the Great War that allowed Wyeth to peer into Kuerner’s conscience. “Andy,” Karl asked, with “a far-off look” in his eyes, “did you hear that snapping?” The sound in Kuerner’s head was barbed wire being cut. He had a story to tell of the trenches, of opening fire on a battalion of French soldiers he knew only as the sound of snapping in the dark. “God, I felt I was there on the western front sitting with him,” Wyeth said. “That story broke me loose of where I was.”

|

Big Top, 1981 ... "I saw this wagon one night in the moonlight . . . It’s an authentic wagon of 1812, in which the Du Pont company used to haul [gun] powder. That wagon evoked vivid memories of circuses." -- Andrew Wyeth

|

Big Top, 1981

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

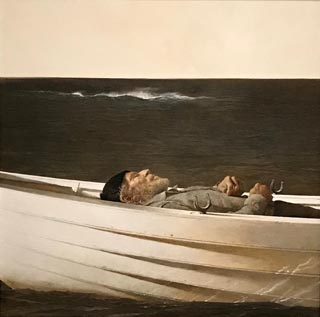

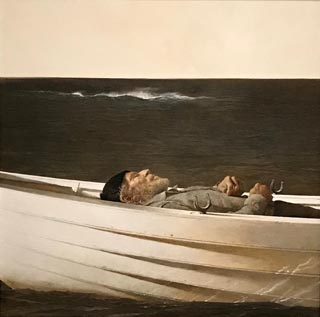

Adrift, 1982

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Adrift, 1982 ... Wyeth explained this was a portrait of his dear friend, Walter Anderson, merely asleep in his dory. But what we see is a lifeless body reverently laid out in a coffin-like boat that is conspicuously without oars. The only logical explanation of the scene is death, perhaps the funeral of an ancient mariner at sea. The painting was a strange studio construct. But in the background Wyeth added white-crested combers breaking over a submerged ledge that was known to local fishermen as “the Brothers,” a deliberate and touching reference here, no doubt, to the closeness Wyeth felt to Anderson.

|

North Light, 1984 ... A great window fills the north side of N.C. Wyeth’s grand painting studio. It speaks of the famous man’s outsize character and ambition. The elder Wyeth had designed and built his Chadds Ford home and studio with money he received from his very first commission, in 1911, the celebrated illustrations for Treasure Island.

|

North Light, 1984

Brandywine River Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA |

Little Africa, 1984

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

Son Andrew grew up here and formally entered his father’s studio as a student on October 19, 1932. After N.C. Wyeth was tragically killed by an oncoming train, on October 19, 1945, his children maintained the studio ever after as a shrine. When Andrew Wyeth painted this symbolic “portrait” of his father, he was in a deeply reflective mood. The secret of painting Helga was now strained to breaking, and Wyeth’s art making and personal life would soon be upended.

Little Africa, 1984 ... Wyeth painted Little Africa as a rebellious act against his late father. The title refers to the old black settlement in Chadds Ford, largely gone by this time. He had painted Bill Loper and Adam Johnson there. Loper’s steel arm hook represented an unforgettable moment of contention between the Wyeths—father and son, artist and teacher.

In one of Andrew’s earliest efforts, a painting of Bill Loper with his arm hook on full display, an angry N.C. Wyeth took it upon himself to rubout the menacing detail. He considered the hook unseemly, too real for art. N.C. Wyeth often voiced his disappointment in his son’s deadpan realism. Too young and submissive to challenge his father’s intrusion into the first Bill Loper painting, Andrew Wyeth finally settled the score decades later, with this defiant still life.

|

Airborne, 1996

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR |

Airborne, 1996 ... The setting is the Wyeth’s house on their private Benner Island in Maine, which they purchased in 1990. Betsy had assembled a house from reclaimed buildings from both Maine and Chadds Ford, basing it on Henry Teel’s old house on his ancestral Teel’s Island, where Andrew and Betsy had often visited the aged lobsterman. Teel lives on here, specifically in the glass globe and lightning rod, which Wyeth had earlier painted on Teel’s rooftop in 1950 in Northern Point (on view elsewhere in the exhibition), and a weathervane made from one of Teel’s own oars. Benner Island was designed to evoke an earlier time in the Wyeths’ lives. Into this immaculate, carefully staged world, however, chaos has been inserted in the flying feathers.

|

Wheel Gate, 2007 ... Ice plays with our perception here, and Wyeth’s manipulation of ink and paint makes it difficult to read the picture as anything but an abstraction.

Try orienting yourself. The view is to the old wheel gate of the gristmill on Wyeth’s property on the Brandywine River in Chadds Ford. When the mill was in operation, the race water would rush, swift and powerful, through the open gate, through the mill, and then turn the huge wooden waterwheel inside.

Crow Tree, 2007, ... In painting a dead tree, Wyeth depicted the ravages of time, possibly as a self-portrait done in Maine the summer of his ninetieth birthday

|

Wheel Gate, 2007

Collection of Shelly and Tony Malkin |

Crow Tree, 2007 (study for Eagle Eye)

The Andrew and Betsy Wyeth Collection |

An eagle’s aerie, the tall tree required a great expanse of paper, and this is one of the artist’s very largest watercolors. There is something defiant in Wyeth’s impressive artistic statement here—at ninety he is proudly upright and in full command of his artistic powers.

|

| Seattle Art Museum Wyeth Exhibition page | Back to the Top |