|

Bodega Bay Heritage Gallery Monthly |

Homepage | Contact Us | Our Location

| A-B | C-D | E-G | H-He | Hi-J | K-M | N-P | Q-S | T-Z |

California/American School | Alpha Listings of Artists | Recent Acquisitions

Watercolors | Farm Scenes | Coastal | Deserts | Mountains | National Parks | Still Life & Portraits

Previous issues: | December | November | October | September | August | July | June | May | Apri

|

Bodega Bay Heritage Gallery Monthly |

| In this issue: |

- New Gallery Exhibit: Come to the Sonoma Coast and see the Desert |

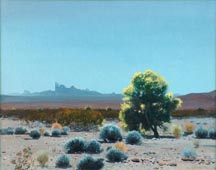

John W. Hilton |

Come to the Sonoma Coast Desert Painters exhibit based on Ed Ainsworth's 1960 book, Painters of the Desert a collection of biographical sketches |

James Guilford Swinnerton |

Conrad Buff |

Carl Hoerman |

* * * * *

Author Larry Hughes previews his upcoming book

discussing John W. Hilton's Calcite Mine during WW II

But for the kindness of strangers and traffic accidents, John Hilton might have starved to death. Living in a ramshackle abode built by his own hands during the Great Depression, he learned from his Cahuilla Indian friends how to live off the land, and from his own inner instincts how to trade the fruit of his eclectic interests in horticulture, minerals, and art for food. Not to mention the spilled fruit from produce trucks that frequently underestimated the sharpness of the bend in old Highway 99 in front of his house. But it was John’s lifelong interest in art, brightened by the sensual palette of the desert he’d come to know and love, that had begun to give him focus in life and put food on the family table. That is, until the war.

|

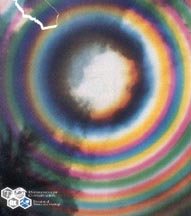

An assembled Optical Ring Sight with a filter used on antiaircraft guns and merchant marine ships. |

The target pattern formed by Polaroid's Optical Ring Sight |

Pearl Harbor changed everything. His process of artistic growth, painfully but faithfully extracted through the tutelage of Fechin, Swinnerton, and others, was supplanted by war matters. After advising Gen. George Patton for a while, John received a phone call from Dr. Harry Berman, a Harvard mineralogist. Could John ship all of his stock of a certain mineral, calcite, that he’d collected from the southern Santa Rosa Mountains a few years back? John had no idea why Harvard would want those old clunker specimens. But the next day, Berman showed up, and John had his answer.

Berman produced a circular optic, no bigger than a fat poker chip. Looking through it, he beheld a concentric series of rainbow-like rings that glowed with an almost electric intensity. Berman explained that this was a new gunsight invented by his friend, Edwin Land, the head of Polaroid Corporation. The Optical Ring Sight was made by sandwitching a thin section of calcite between Polaroid sheets. John knew the basics once Berman explained: that calcite’s birefringence splits the light passing through it into two rays, and a phenomenon known as interference produces rings that can be used to encircle a target. And it was no ordinary gunsight; the rings focused at optical infinity, where the incoming plane was, and the rings stayed put if you were shaking your head back and forth during the violence of antiaircraft fire. It was a perfect solution to the Navy’s need for an inexpensive, simple, instantly deployed sight. There was only one problem: Polaroid didn’t have enough calcite.

That’s where John came in. He had mining claims at the only optical calcite locality Berman had any hope of exploiting within the next few months. Berman had several other prospects, but John’s mine at Palm Wash in the Santa Rosa badlands west of the Salton Sea was Polaroid’s best hope. And so, John Hilton, formerly a struggling landscape artist, became a struggling miner. His heart was not really in it. Unlike other Hiltonesque pursuits, this wartime conscription crimped his independent style. He was better with a palette knife than a rock pick. He shipped back some excellent calcite but not in the quantities needed. In late 1942, Polaroid sent a mining engineering team out to take over the work and expand the mine. John stayed on as a prospector. |

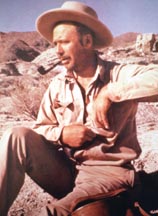

John Hilton in a rare idle moment at the calite mine |

The work was hard, the heat intense. Although he had never eaten better, thanks to the mining camp’s exemption from meat rations, John’s privation of paint was never more wasting. He sketched when he could, despite being regarded by some miners as a gringy artist. He struggled with paint, yet to find his artistic voice amidst the visual din of uncertain swipes of his palette knife. He was painfully aware of the artistic growth that needed to come, but equally aware that the war had to come first.

Yet on one occasion, John found solace in an impromptu plein air art camp. The noted social realist Irwin Hoffman was the brother of the mine operators, and came to Palm Wash to recuperate from a back injury. He sorted calcite in the afternoons but otherwise was free to paint the miners and landscape in watercolor and oil pastel. At the same time, John’s friends, Ed Ainsworth and the accomplished painter Clyde Forsythe, came out to visit. John did not recount his feelings of this encounter, but they must have been a severe mixture of angst and ecstasy. Like the song, Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, no one can sympathize with a struggling artist like another artist. Imagine the banter and artwork that must have arisen around the campfire during those days! (I am not aware of any of Hilton’s work from this era that survived; Hoffman left about a dozen works that I’m aware of.)

Hilton’s calcite was one of the many small components of the military victory that defeated the world’s fascist nightmare. The Optical Ring Sight was used on shipborne antiaircraft guns, airborne gunnery, and on the bazooka, seeing action in Europe and the Pacific.

For Hilton, war’s end brought a special sweetness. It meant he was now free to paint again, a freedom that would bring him unimagined success, both artistically and financially, in the years to come.

Note: The story of John Hilton, and of the many others who contributed to Polaroid’s Optical Ring Sight, is told in the upcoming book, Rings of Fire, by Larry Hughes. The book is about the eclectic collection of disparate individuals who, during a time of crisis, came together for a common purpose in improbable ways with remarkable results. If you have any information on any of John Hilton’s art work during WWII, Larry would appreciate hearing from you. You may contact him at lhughes@ensafe.com or write to: Larry Hughes, 5724 Summer Trees Dr., Memphis, TN 38134.

* * * * *

Jimmy Swinnerton

A teacher of great painters and a teacher for us all

If Jimmy Swinnerton was the Dean of the school, John W. Hilton was one of its brightest students, and no teacher could ask for a more eager and willing student. When given the opportunity, John, thirty years younger, would drop all that he was doing and accompany his mentor on sketching trips into the desert, often accompanied by other painters such as Maynard Dixon.

In 1903 (a year before John Hilton was born), Jimmy Swinnerton came to the California desert as a very ill twenty-eight year old refugee from New York City.

Swinnerton began his artistic life in San Francisco. He trained at the California Art School alongside fellow classmate and lifelong friend Maynard Dixon. Swinnerton was noticed by another San Franciscan, a newspaper man named William Randolph Hearst, and Hearst hired Swinnerton to be a cartoonist for his New York newspapers. Swinnerton was a hit in the East, and was building quite a notable career for himself when he received some devastating news. Three doctors informed him that his infection with tuberculosis would end his life within a month.

At the time, many were dying of TB, and Swinnerton reacted to the news with action. He immediately removed himself to the dry climate of the deserts east of Los Angeles, and the effort paid dividends.

At the time of his arrival, Palm Springs was a small cluster of tents, and the Indians far outnumbered the “11 white men” Swinnerton counted upon his arrival. There were no freeways, golf courses, wide manicured boulevards lined with high end shops, no freeways. And the desert skies were of course free of air traffic. In those days, horses, mules, a large canteen and stout determination were necessities for survival.

But for Swinnerton, the desert was his ticket to a long and fulfilling life. His health and his spirit thrived in his new environs, and his celebration of life was the center of his character and became the keystone of his art.

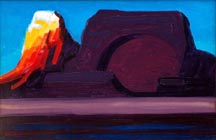

He wanted to share the life and beauty he found in the desert, and he did so by putting his artistic skills to work. He created canvases dominated with desert tones and shapes with stark light and shadow, but counter-pointed with the newly sprouted greens of desert plant life. Eastern critics at first did not respond well to his work, clinging to their preconceived ideas of the desert being a wasteland. But Swinnerton persisted, convinced other painters to come to the desert, and together, their works changed minds.

Swinnerton not only tried to turn people’s conception of the desert as a wasteland. He used his skills as a cartoonist to counter predjudicial notions about the desert Indians. His cartoon strip, Canyon Kiddies, was created to dispel the perceptions most associated with the desert. The little Indians of his comic strip possessed a natural kinship with the desert, believing the desert’s creatures were their brothers, not to be feared but revered. The Kiddies seemed oblivious to what most would consider hardships of heat and cold. Even the storms of the desert were friends. Through the Canyon Kiddies, Swinnerton was able to inform and instruct people without preaching, that the natural world possesses great beauty.

So, this man who wasn’t expected to see his thirtieth birthday lived to be ninety-nine. This sickly east coast sophisticate came to the empty California desert in 1903, and became a teacher for us all, through paint and cartoon, of the desert’s diverse beauty and life. His spirit, so evident within his art, was infectous, inspiring his fellow artists of his own generation and beyond. What remains today is his art, his vision which celebrates life, hope, and of promise, qualities the dean of any school should possess. His paintings still speak to us.

| Links to Current Museum Exhibits Relevant to Early California Art | |

Palm Springs |

Irvine California Mission, October 23 - March 15, 2008 http://www.irvinemuseum.org |

| Pasadena Benjamin Chambers Brown, October 10 2007 - January 6, 2008 http://www.pmcaonline.org |

Monterey The Monterey Cypress: Celebrating an Icon Masterworks of California's Painting by Armin Hansen and William Ritschel Dec 22, '07- Jun 22, '08 http://www.montereyart.org |

Oakland |

Sacramento Permanent Exhibit: Early California Art Edwin Deakin: California Painters of the Picturesque Jan 28 - April 20, 2008 http://www.crockerartmuseum.org/exhibitions/permanent_california.htm |

| Santa Rosa Rotating history gallery http://www.sonomacountymuseum.com |

Ukiah Grace Hudson permanent collection http://www.gracehudsonmuseum.org |

San Francisco |

Los Angeles Jake Lee Exhibit http://www.camla.org |