homesteads were far between. The street signs were sandblasted and unreadable, even when I aimed the headlights directly at them–and Kathi didn’t remember the street names anyway.

We blundered along for awhile, until a dark structure loomed ahead on a hillside. Kathi said: “Pull in here by this row of trees.” A strange orange moon was rising over “the loneliest little house on a hill,” as John Hilton once described it. The place now looked like a scary tweakers’ den with shredded toys and junk strewn everywhere.

Kathi pointed and said: Here was my dad’s garden. Here was the mineral water pool where James Cagney came to swim; here was the studio where I painted when I lived here. Sometimes my dad’s friends flew in and there were two Lear jets parked on the landing strip out back.

|

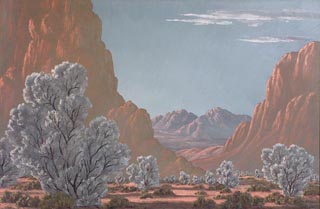

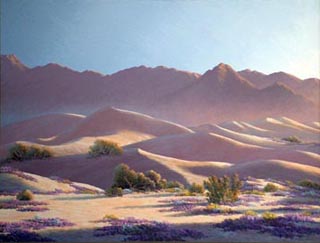

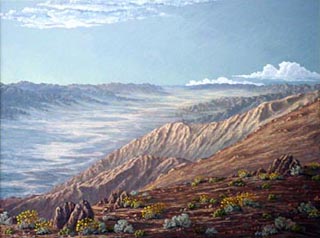

Kathi's "Enchanted Desert"

Oil on canvas, 24 x 36 |

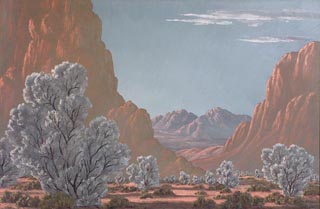

Kathi's "Touched by His Grace"

Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 |

The three of us sat in silence. I made a U-turn on the old airstrip and drove back to town, awed by this glimpse into the mythic life of the first family of desert painters. Kathi—who now lives in Roosevelt, Utah–deserves to be written about without mention of her dad on occasion. She has an art career all her own.

|

John and Kathi at their first joint exhibition |

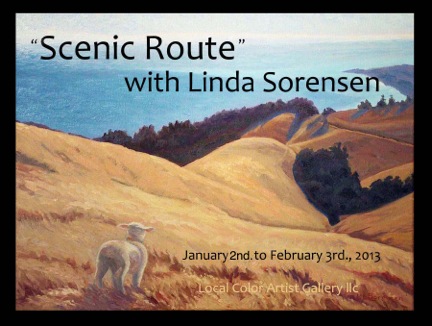

At Dan’s Bodega Bay gallery, co-owned by his wife Linda Sorensen, customers often prefer Kathi’s pastoral paintings over the work of John Hilton. Still, you can hardly talk about one without the other.

|

Young Kathi and her prized tricycle |

The Hiltons shared a devotion to the palette knife, a love of pink skies and a heaping of family lore and myth. Names like Agnes Pelton, Clyde Forsythe, Maynard Dixon, Nicolai Fechin and Bill Bender weave in and out of John’s life and Kathi’s childhood memories.

Like many stories of dads and daughters, this one has its share of sorrows. While John Hilton gave Kathi a calling and a name, he also abandoned the family when she was young and did not always encourage her art. When she entered a poster contest as a young woman he remarked: “It’s good, Kathi, but you really can’t draw.”

This sometimes-difficult dad also happens to be the best-known of the desert artists, not just for his paintings but also for his shtick. Hilton’s early years spent in China with missionary parents infused him with a love of the exotic, and he later mined the themes of old souls, reincarnation, and the occult to win audiences.

|

The man mined calcite in Borrego, captured Gila monsters in Baja, sang in Cahuilla and had a poltergeist named Felica. (“Felica was my friend too,” says Kathi.)

|

|

His story is told by Katherine Ainsworth in The Man Who Captured Sunshine with the tall tales left unchallenged.

One such tale: Hilton was friends with Cathedral City’s Agnes Pelton, but he was no fan of abstraction in art. To make his point, he once painted a gag Pelton, slapped on the title Cosmic Metamorphosis, and sold it instantly for $350 (or so he said.)

In another bit of stock showmanship, Hilton held a ceremony each year in which he burned his rejected paintings in a big bonfire in Box Canyon. The bonfire routine was not unique to Hilton but was practiced by other theatrical painters such as Tucson’s Ted de Grazia.

|

John Hilton with guitar, Eunice Hilton

(with dark hair) seated on the bed

at the Thermal art and gem shop. (early 1940's) |

Born in North Dakota, Hilton first came to Valerie Jean corner in Thermal in 1931. Valerie Jean’s was the famous date shop where old Route 86 meets Ave. 66. Hilton opened his gem and art shop across the street. The ruins of the gemshop were leveled a few years ago; the date shop building still stands.

Hilton’s first wife was Eunice, a nurse. The couple’s daughter Kathi, named after Katherine Ainsworth, Hilton’s biographer and wife of newspaperman, Ed Ainsworth was born in a Mecca doctor’s office in 1939 and spent her early years in the art and gem shop amidst Chuckwallas, geodes and magnetic rocks.

|

Kathi and her grandmother Hilton in 29 Palms |

Her brother, John Philip Hilton, also an artist, died as a young man. Kathi was born into a perpetual party. An early photo taken at the Thermal home and gem shop shows her mom and dad seated on the bed and presiding over an artists’ party. Is that Maynard Dixon in the corner with the black hat? Kathi says she doesn’t know. Dixon was on the scene at the time, but she was just a kid and often hid under the bed while famous painters sang along to John’s guitar.

Of her father’s friend Maynard Dixon all she remembers is: “I loved his voice.” She remembers Clyde Forsythe as the man who brought her peppermint candy. Marjorie Reed was her sometimes-baby sitter. And, yes, for all you desert art gossips, her dad did have a fling with the legendary stagecoach painter.

The PT Barnum of California art, John palled around with guys like Zane Grey, President Dwight Eisenhower (a fellow painter) and General George Patton and was always going off hunting mummies or on other adventures with LA Times reporter Ed Ainsworth.

Hilton’s career was helped along by Ainsworth, author of the classic on the Smoketree School, Painters of the Desert. Hilton supplied the stories Ainsworth needed and in turn Ainsworth gave Hilton and friends ink.

|

Hilton was also championed by Harriet Day, the influential director of the Desert Inn art gallery and later the Desert Magazine gallery in Palm Desert. (A neighbor of Agnes Pelton, Day also once ran a curio shop and sold Carl Eytel sketches in Palm Springs’ Indian Canyons.)

Hilton moved out of the family home when Kathi was nine; he and Eunice divorced when Kathi was twelve. She didn’t see her father for four years until she showed up unannounced at a show he had at the Palm Springs Museum. His absence had to hurt, but Kathi was stoic as she told the story over dinner in 29 Palms.

|

Hilton moved to 29 Palms in 1951 after the divorce, choosing the remote town as a place to regroup. He met and married Barbara Hollinger, and became the founding president of the 29 Palms Art Guild and a founder of the 29 Palms Gallery.

Meanwhile Kathi’s youth was itinerant. She went to school briefly in Alamos, Mexico; her dad wrote about those years in his Sonora Sketchbook. She attended the bohemian Desert Sun School in Idyllwild, then a private school in Sherman Oaks, made a foray into modeling in Beverly Hills and took classes at UCLA.

John’s party life continued. There was always revelry going on at the new house in 29 Palms, and though Kathi became friendly with Barbara, she was on the periphery of the scene.

|

The 29 Palms Gallery building,

courtesy of the 29 Palms Historical Society |

Only after moving to 29 Palms did Kathi finally become a painter herself, despite her dad’s initial discouragement. She was 30 years old at the time and recent spinal surgery had left her immobile and dispirited. Her friend Uta Mark encouraged her to paint

Lee Lukes Pickering–author of Colorful Illusion, a valuable history of the 29 Palms art guild–helped her with colors and convinced her to change her name to Kathi with an “I”. “There’s a lot of Kathy’s out there,” Pickering advised.

When she began painting Kathi found mixing colors came easily to her, a genetic gift. Her paintings, made with palette knife, oils and fossil wax, looked remarkably like her father’s. “We found out we had the same mind’s eye,” she says proudly.

|

Kathi Hilton, center, with Uta Mark,

left and Mary Jane Binge, in 29 Palms, 1970.

|

Kathi’s very first show was at the 29 Palms Gallery in 1970. Her father sent orchids and anthuriums from Maui, where he was living at the time. While initially the senior Hilton had not welcomed her foray into art, he now began to appear in father-daughter shows with her. They even sometimes worked on the same canvas together: a Hilton-Hilton.

After Barbara died in 1976, Hilton charmed a waitress named Janna. Kathi recalls her dad carried gemstones from his gem-collecting days in his pocket and used them to woo women. Yet Janna, Hilton’s new wife, was an unfortunate choice. “She didn’t understand who he was,” says Kathi. When Hilton died in 1983, she discarded his files, photos and letters, a complete history of the Smoketree School of desert art.

|

Bill Bender, a respected desert artist who lives in Victorville, has mixed memories of John Hilton. He sometimes annoyed his friends with his swagger and tendency to hog the spotlight. Yet he brought the impoverished painters needed attention. Painting landscapes is not inherently newsworthy so the desert artists needed a promoter. Hilton was it.

When Bender invited John to Manila and Guam as part of the US Air Force artists program, John took credit for the trip. “As long as he was on stage he was happy,” Bender says. “Still we remained friends right down to the bitter end.”

Kathi Hilton moved to northwestern Utah in the late 1970s and moved into a geodesic dome with her husband, Boyce Garvin. She showed her work widely in the West, exhibiting with the Death Valley 49ers and the Women Artists of the West, among others. Boyce died in 2007; Kathi still lives and paints in the dome.

|

Kathi Hilton at a reception in 29 Palms,

Labor Day, 2012

|

When Kathi returned to 29 Palms recently after decades away, it was like the reunion scene from the Wizard of Oz. She held court in the adobe gallery–scene of her very first show–surrounded by her small bronzes of yucca and palms, her own paintings, and a few of John’s. The walls were lush with images of verbena, dunes and smoke trees glowing nearly white.

A parade of indistinct faces approached Kathi. Her smiles dawned slowly as she recognized people from the past. In a greeting typical of others, 29 Palms historian Pat Rimmington said to the artist: “I haven’t seen you for 100 years!”

Along with people from the early days, there were many new devotees who hold the name “Hilton” in near-reverence. Gary Cardiff of Palm Desert asked Kathi to sign his books on the early painters, and also purchased three of her paintings. He told her his grandmother, Pearl “Mona” Stuart, worked in the Desert Magazine gallery, one of the places John Hilton got his start.

|

As Kathi greeted well-wishers in the crowded room, her father was never far from anyone’s mind. There are photos and a bust of her dad, done by Cyria Henderson of Palm Desert, in the gallery hallway. Even John’s remains are here. When Hilton died Kathi flew her dad’s ashes back home and placed them in a compartment under the bust.

It took many years for Kathi to comes to grips with a disjointed childhood and the overpowering influence of the Man who Captured Sunshine, but in the end the sunshine on display in 29 Palms belonged to her alone. As Desert Magazine said in 1978: “Kathi creates a luminosity of her own.”

|

Kathi posing at the reception for her work at the Twentyine Palms Art Gallery in September |

Ann Japenga's Website

http://www.californiadesertart.com |

Kathi's Show at Bodega Bay Heritage Gallery |

Kathi's webpage |

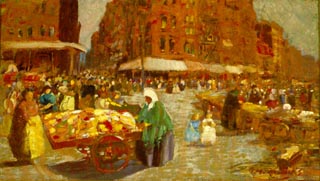

But any side by side comparison of Doug's work and the Ashcan painters requires an appreciation of the similarities and differences between them, for the Ashcan painters lived in a different time, painted for different purposes, and had a different audience.

The Ashcan painters did not think of themselves as social commentators. They viewed themselves as urban reporters with paint and canvas, showing images of vibrant realism. They were visual beat reporters. They weren't out to make judgements. They thought of themselves as having their hand on the pulse of an exciting, thriving and throbbing New York scene.

|

Robert Henri Snow in New York Robert Henri Snow in New York |

Their work showed determined images of an ascendant people in tough settings, but people with strength and determination equal to the task of survival and advancement. They painted subjects burdened by their grinding reality, yet tenacious and resilient enough to endure and thrive.

|

Edward Hopper The El Station |

George Luks Houston Street |

Doug Rickard has a different story to tell. Using technologies never dreamt of by the Ashcan painters, Doug peers into the overly neglected and decaying centers of American life.

He shows once thriving cities have which have descended into a decaying urban shell, the burned over scorched launching pads once used by those who have moved on to brighter and better lives, abandoning old neighborhoods and neighbors to serve as custodians of what remains. If Doug's work bears a message, this might be it, "A nation of wealth need not balance its glories with shame, neglect, and abandonment."

|

In today's modern age, the new term "telecommuting" is the way many people work. It's amazing that Doug has accomplished much with his photography, without lugging grear through airports, or waiting for the light and weather to cooperate. To think he's done much of this with a computer, a camera, a tripod and a vision, all without leaving his Sacramento studio, is a commentary and an artistic statement in itself.

Doug's work could be easily dismissed as yet another wrinkle in this expanding electronic age, but I find his edited Google images imaginative, daring, bold and challenging. It is worthy of your consideration and discussion. Check out his website and view his works at SF's MOMA soon.

|

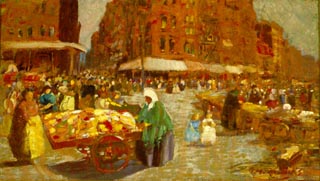

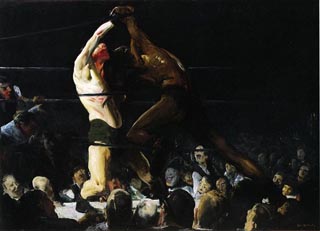

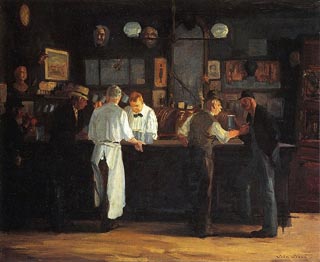

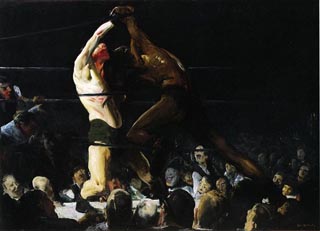

George Bellows Members of this Club |

William Glackens Italio American

Celebration Washington Square |

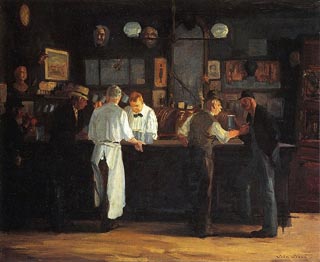

John Everett Sloan McSorley's Bar |

| Doug's Website |

|

Back to the Top |

Speaker Boehner beneath Washington's Gaze

by Daniel Rohlfing |

Portrait of George Washington

by Gilbert Stuart 1755-1828

The original painting is in the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution,

the one in the House of Representatives

is a copy done by Gilbert Stuart.

A third copy is in the White House Collection, saved by Dolly Madison when the White House was burned by the British in 1812

|

This recent photo of Speaker of the House John Boehner standing in front of Gilbert Stuart's "Lansdowne Portrait" of President George Washington, commissioned in 1796 has grabbed our attention.

This painting shows the occasion of President Washington's refusing to accept a third term as President. Looking beyond the portrait to Washington himself, we find a brave man of deeply held convictions with decades of outstanding public service, but a man able and willing to compromise.

|

House Speaker John Boehner

recently addressing the "fiscal cliff"

in front of a House of Representative's copy of

Gilbert Stuart's Portrait of George Washington,

a depiction of the first president

announcing he would not seek a third term.

|

The photo to the left shows Speaker Boehner recently after the 2012 elections, addressing the controversial issue of the "fiscal cliff," something that many believe will be the occasion for either compromise of catastrophe. Our most optimistic sense is the Speaker is well aware that he is giving his remarks while standing in front of a portrait of one of America's greatest compromising leaders, George Washington.

In fact, among the nation's founding fathers, we find a long legendary list of fearless and determined men of

|

principal and conviction. But had it not been for their ability to work together and find compromise, the new nation they sacrificed for and founded would have certainly faltered and failed. Uncompromising staunch insistence on any one point of view would have guaranteed failure.

|

Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851)

December 25–26, 1776

Painting by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze 1816-1868

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

|

As General of the colonial forces in the War for American Independence, Washington lead an ill equipped, underfunded, and poorly trained force against the British Army, the best trained and well equipped military force of his day. In a similar fashion to the lament of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Washington had to go to war with the army he had, not the army he wished he had. For Washington, his daily decisions are testament to his sense of compromise, his keen ability how to make do and how to get by with less than what a given situation called for. This ability (today many call it "thinking outside the box") was a major element of his success.

Many history teachers have said Washington was successful only due to his excellent leadership, lots of old fashioned luck, and considerable assistance from the French. A closer look might teach us that a good part of his "luck" was the ability to compromise.

|

As President of the Constitutional Convention, Washington helped the young nation in replacing its weak Articles of Confederation.

Under the Articles, the new nation was piled high with war debt. The major weakness in the Articles of Confederation was the inability of the national government to tax its citizens or its member states. Talk about a "fiscal cliff."

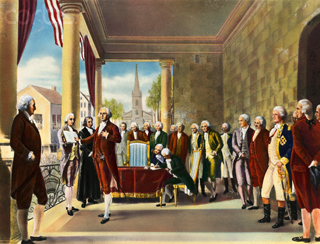

To solve the problem, a Constitutional Convention was called. Washington consented to serve as President of the Convention. In the end, this convention was successful only because of two major compromises, one called the Great Compromise between large and small states, and the other was the Three-Fifths Compromise between slave-holding and non-slave-holding states. Without these two compromises, the Convention and the young nation may well have dissolved into thirteen tiny separate nations.

|

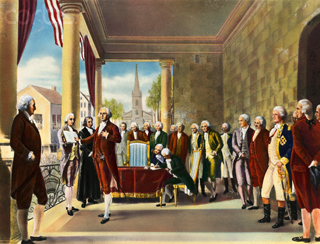

Signing of the Constitution (1940)

Painting by Howard Chandler Christy 1873-1952

(the U.S. House of Representatives) |

Capitol architecture ... Form follows Compromise

A Senate and a House based respectively on equal representation and population |

The Great Compromise was a dispute between large states and small states regarding how Congress could be shaped. Large states wanted a Congress based on population, the larger the population a state had, the larger would be its say in Congress. The smaller states wanted Congress based on equal representation, each state having an equal say. The issue threatened the convention, and it came very close to breaking up the Union. What saved the day was The Great Compromise, providing the views of both sides of the disagreement. The Convention provided for a House based on Population, and a Senate based on equal representation. Neither side got all what they wanted, but each got something they did want.

|

As President, George Washington served two terms. He did not belong to a political party, and felt strongly that political parties would not serve the nation's interest. But as President, he often had to endure disagreement within his cabinet, between the federalist wishes of his Secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, and the state's rights views of his Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson.

Throughout his life of public service, Washington was a skillful negotiator and gifted at the art of compromise. "Compromise" is not a dirty word, but rather it is most noble and useful. Compromise forged by men of strong conviction enabled our young nation to move forward.

|

Washington's Inauguration, April 30, 1789

Painting by Senor Ramon de Elorriaga,

(the Granger Collection, New York ) |

| Back to the Top |

Robert Henri Snow in New York

Robert Henri Snow in New York